Through the Glass Ceiling: Georgian Women and Careers

Career advancement issues facing Georgian women is a topic of immense discussion. These issues get even more complicated when a woman, born and raised in Georgia, chooses a profession which is typically considered to be a man’s job.

Ekaterine Kvlividze, 34, experienced career-related barriers as the first female military pilot in Georgia. There have been ups and downs; promotions and demotions; cases of solidarity and sexism… until she felt she could no longer endure it. She didn’t surrender, she just changed her path. Now, the woman in the military is back – only in politics.

A Small Town Girl with an Unusual Dream

“Back in school, I always wanted to join the military, to wear the uniform, and defend my homeland. I thought it was the best way to make a contribution for my country,” - she reminisces.

Born and raised in Sagarejo, a small town in Kakheti region of Georgia, Kvlividze, still a schoolgirl, took her free time to learn about the military. That’s how she initially found out about the military aviation.

The fantasy of being a female pilot defending her country seemed fascinating yet improbable. However, she felt she had to, at least, try. The very first step was to pluck up the courage and tell her family about her career goals.

“I was initially scared to tell my family. I didn’t know how they would react. Over time, I let them know who I wanted to be, only in a joking manner. Nobody had a negative reaction, but they didn’t take it seriously. They thought I would grow out of it… I didn’t,” - she recalls.

Kvlividze’s mother wanted her to become a pharmacist. “I still don’t know why. I don’t have anything in common with that job. She just saw me that way,” – she adds. Her biology teacher, on the other hand, had a brighter view of her future and advised her to become a doctor, while her Georgian literature tutor thought she would make an excellent schoolteacher. In reality, all her dreams and ambitions were connected to military.

Turned out, persuading her family to support her career goals was the easiest obstacle she had to overcome. It was 2003, and women could hardly apply to military or aviation schools.

The National Defense Academy, where she initially wanted to apply, didn’t accept any women. “They made some budget-related excuse. So, I tried to get into civil aviation. They wouldn’t accept a woman in the flight training faculty either, because they didn’t have an experience of training women. So, I applied to the school of engineering at Georgian Aviation University,” - she says.

Budding aviation engineers were all men, with one exception: Ekaterine Kvlividze was the only female in her study group. Initial reactions were doubtful, but gradually changed: “At first, everyone was looking at me like I was some sort of an alien, who had no idea what she got herself into… However, after finishing the first semester with maximum grades, they started to take me seriously.”

The Triumph

Ekaterine was in the fourth year of her studies, when the Ministry of Defense of Georgia announced a course for young pilots. Indeed, they planned to only accept males. Nevertheless, Kvlividze applied.

“They thought someone applied with a wrong name. That’s why they contacted me,” - she reminisces with a grin. “I expressed my motivation to become a pilot. There was one open-minded commander who gave me a chance. I had to go through a trial period after which they would decide whether to accept me or not. In the end, I got accepted.”

The first flight brought a sense of victory. “I felt a firework of emotions,” – she recalls. There were multiple flights afterwards, which, for several years, became a usual part of her life.

In her own words, Kvlividze has never been a careerist: “I always enjoyed the process too much to care about the finish line. I loved doing my job, and success usually came on its own.”

A Different Perspective

After a long time of active service, Kvlividze wanted some time off. “I guess we all have those moments, when we want to stay home, in our comfort zones,” – she says. However, an unexpected opportunity came up, which she couldn’t resist.

“I went to military trainings in the US, where I had the opportunity to look at my profession from a whole new angle. In Georgia, I struggled with gender inequality, while in the US, the absolute equality of men and women in the military blew my mind… One of my instructors was 5 months pregnant, but would run over 8 miles each morning. Another returned to the trainings 2 weeks after giving birth. Such things are completely unimaginable in the Georgian context,” – she recalls.

On the other hand, Kvlividze observed that the military service in the US was far more valued than in Georgia: “Whenever I went out with a uniform, people approached me and said: “Thank you for your service”. They had no idea who I was or which country I came from, but they expressed gratitude nevertheless.”

The Scandal

Kvlividze returned to Georgia with an enriched experience, but naïve expectations. She wanted to share everything she learned in the US, but nobody cared or listened.

“I turned out, I was demoted, and my flights were cancelled. Whenever I proposed new ideas, responses were cynical. I was preparing to acquire a new technique on helicopters, but they rejected. When I asked for a reason, they said they wouldn’t spend their scarce resources on a woman,” – she tells.

It was the last drop. She resigned. After spending almost 12 years in the military aviation, she left her beloved job. In response, the Ministry sued her for breaching the contract. The fine was huge, and kept increasing before the court would make a decision.

“I argued that the Ministry fulfilled none of its responsibilities. Their unfair decisions made me leave. Then they made complaints. Eventually, we needed to negotiate, but the Minister wouldn’t talk to me. So, I approached him in the Parliament, and he had no choice, but to listen. In the end, the Ministry withdrew the appeal,” - she recalls.

Kvlividze didn’t expect the amount of support she received from the society: “I can’t even remember a single negative comment. Everyone was trying to comfort and empower me.”

A New Path

Switching from military to civil life was tricky. She had to adapt to a new reality, which made her see the everyday problems she hadn’t been aware of. Looking for ways to contribute to her community, she decided to get into politics, and is running as a Majoritarian candidate in her region. Again, she’s the only female running in the district.

“As the election date approaches, the campaign keeps getting more and more exciting. I meet a lot of people, and listen to their problems and expectations… No matter the outcome, I will do my best and continue serving my community,” - she says.

Kvlividze thinks that generally, becoming a member of the Parliament should not be based on gender. However, gender quotas are temporarily necessary in order to break the ice: “I hope that over time, seeing an increased number of female politicians in the Parliament will encourage young Georgian girls to speak up and serve their community.”

The Bigger Picture

Ekaterine’s story may be engaging to many, but the obstacles she had to overcome aren’t unique. In fact, they point to significant problems faced by Georgian social and political landscape in terms of gender bias and inequality.

According to the latest data from the National Statistics Office of Georgia, approximately 51.8% of Georgian population are female. Despite a slight majority over the male population, women in Georgia are significantly less economically active than their male counterparts. Held by UN Women, the 2018 research on Women’s Economic Inactivity in Georgia showed that although Georgian women are more likely to receive higher education than men, women’s participation in Georgian labor market is 29% less than that of men.

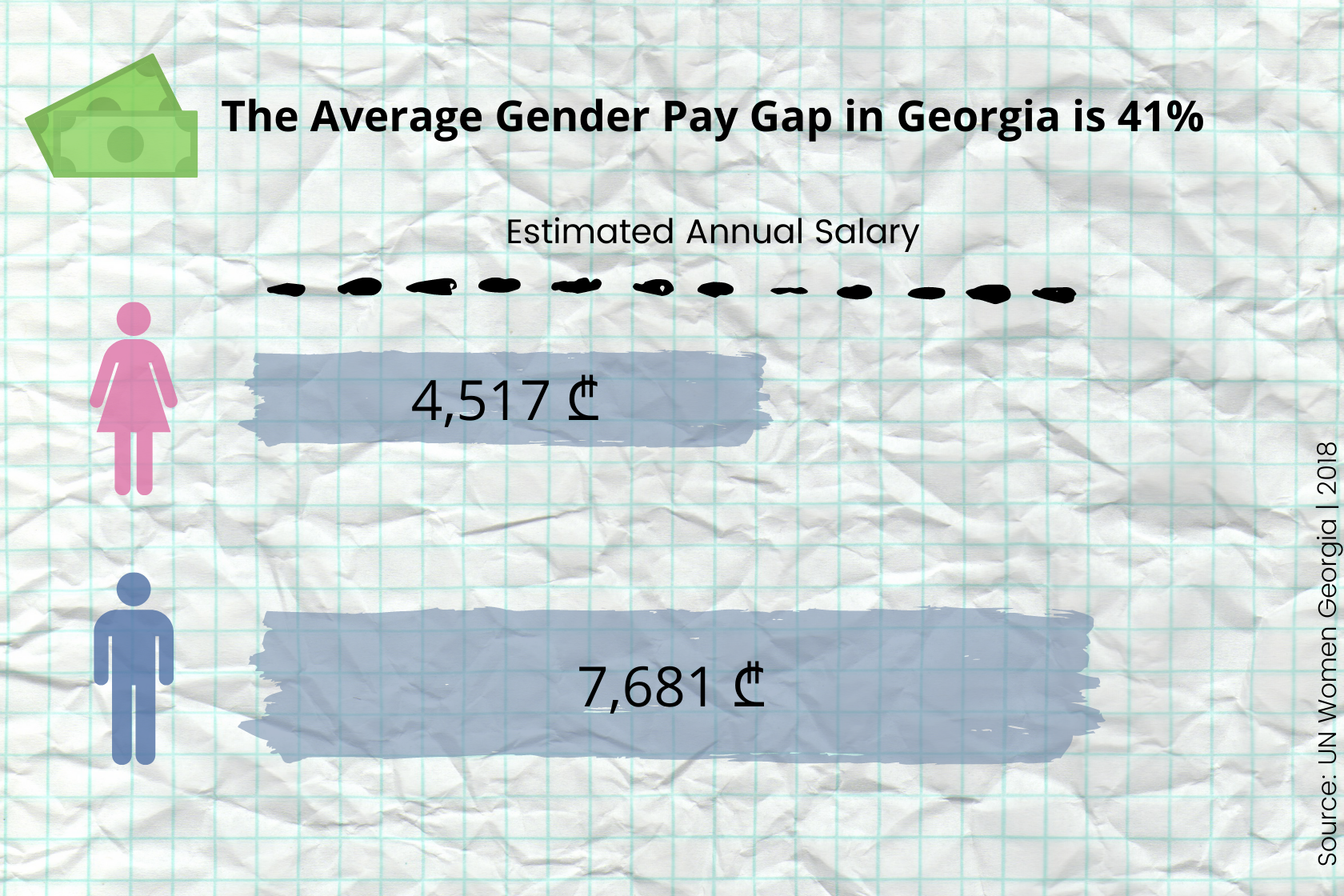

The research links women’s economic inactivity to the gendered division of labor within the Georgian society. In addition, because of the gender pay gap, women tend to have weaker financial incentives. In fact, the average pay gap between men and women in Georgia is 41%. As stated in the research, if Georgian men and women received equal payment, women’s economic engagement would, most likely, increase, which would consequently uplift the Georgian economy.

The 2020 study on Career in Civil Service and Gender Equality conducted by IDFI, found that females in Georgia often demonstrated better academic performance at education institutions than males. However, their career development and academic achievements weren’t proportional, and women got held back if they joined the civil service. Besides, the study observed that if a competent woman with no influential contacts got employed at civil service, she was less likely to advance in her career, and would eventually decide to leave the civil service.

According to the 2014 research on Gender Discrimination in Labor Relations issued by Article 42 of the Constitution, gender inequality in Georgia is acknowledged as a reality, but hardly perceived to be a problem. Instead, it is considered to be a part of cultural heritage, while the attempt to diminish it would put traditional values at risk.

Cultural Influences

Film critic Theo Khatiashvili gives an insight on how cultural aspects might be reinforcing gender bias.

“The Soviet ideology greatly interfered in people’s lives. At first, the propaganda claimed to have emancipated women and implemented gender equality. However, the initial doctrines gradually became distorted,” – she says.

While some restrictions have actually been abolished for women, they came to encounter a whole new wave of challenges, Khatiashvili adds: “The regime required women to be active citizens, but didn’t exempt them from the invisible labor of housework.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, according to Khatiashvili, society faced a cultural confusion.

“People had a hard time prioritizing a myriad of problems, including women’s roles in society. It is reflected in the post-Soviet Georgian films as well. Oftentimes, women are portrayed either as struggling and aggressive or silent and oppressed types,” – she explains.

Khatiashvili thinks that over the years, many positive changes have been made in terms of women’s rights. However, we still have to solve numerous issues in order to achieve complete equality: “We know lots of active, successful women in Georgian society. Unfortunately, many of them take their positions for granted. Remember the debates around gender quotas in the Parliament? Even some eminent, influential women oppose it. I guess they are not properly informed about the history of feminism. Otherwise, they would know that their own success was also made possible by the steps taken towards gender equality”.

Expectations and Role Models

Human rights lawyer and executive director of Partnership for Human Rights, Anna Arganashvili emphasizes the importance of social expectations in terms of women’s career advancements.

“Society often tells women that they can’t achieve career goals and can only be good at household activities. Such statements often internalize within women’s minds. They end up believing that they can’t reach their goals, and consequently, don’t try hard enough to succeed,” - she says.

According to Arganashvili, the women who choose stereotypically “less feminine” professions, may go through even more obstacles. “They usually encounter both visible and invisible barriers,” – she adds.

“For example, a young female pilot may be denied the access to the new equipment or training opportunities. The message is clear: the women aren’t expected to achieve significant success, and therefore, additional resources shouldn’t be spent on them,” – she explains.

As for female politicians, Arganashvili thinks they may be likable – until the moment they decide to speak up. “When a female politician stands for something, they might get attacked not only for their opinions, but also for their gender,” - she adds.

In terms of gender equality, the lawyer thinks there have been small positive changes in the Georgian legislation. However, the executive part remains problematic.

Gender quotas in the Parliament, she thinks, are temporary positive measures. “It has proved to be a successful initiative in many other countries. Until society gets used to an increased participation of women in politics, gender quotas can be helpful,” – she asserts.

Arganashvili also points out another important challenge faced by women today: the lack of female solidarity. “Research tells us that women, who experience inequality, may attempt to rationalize their conditions. That’s why when other women speak up against inequality, they criticize them for doing so,” – she explains.

Changing attitudes in favor of a gender-equal environment, in Arganashvili’s opinion, depends on all of us: “We can all be role models. It’s up to us, what kind of an example we give. The more we speak up against injustice, the better.”

Breaking the Glass Ceiling

In order to describe the barriers faced by women during their careers, both the mainstream media and academic articles frequently use the “glass ceiling” metaphor, which represents the concept of a transparent barrier keeping women from advancing to certain levels at their jobs. The progress is primarily hindered because of their gender.

The glass ceiling issue has persisted for a long time not only in Georgia, but also in countries with rich democratic traditions. According to the 1995 report issued by The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission of Washington, 3 major factors contribute to a formation of the glass ceiling: social barriers, including gender stereotypes and gendered division of professions; organizational barriers, pertaining to the spare use of available resources exclusively for males; and state barriers, indicating the lack of relevant legislation and/or law enforcement.

Nonetheless, many western societies have managed to take progressive measures in order to facilitate women’s career advancements by enacting and executing laws and regulations which ensure that women receive equal payment and a chance to take higher positions.

It’s worth noting that Georgia collaborates with the United Nations in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, which include the establishment of gender equality, provision of decent work and economic growth, and general reduction of inequalities. Therefore, breaking the glass ceiling will not only benefit the women of Georgia, but also the country’s economic growth, and its contribution to the establishment of international welfare.

References:

- National Statistics Office of Georgia. (2020). Population as of 1 January by age and sex. Retrieved from: https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/41/population

- UN Women in Georgia. (2018). Women’s Economic Inactivity and Engagement in the Informal Sector in Georgia. Retrieved from: https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20georgia/attachments/publications/2018/womens%20economic%20inactivity%20and%20inf%20employment%20georgia.pdf?la=en&vs=2746

- IDFI. (2020). Career in Civil Service and Gender Equality. Retrieved from: https://idfi.ge/public/upload/Gender/Web/Gender_ENG%20WEB2.pdf

- Article 42 of the Constitution. (2014). Gender Discrimination in Labor Relations. Retrieved from: http://www.parliament.ge/uploads/other/75/75600.pdf

- Baxter, J, & Wright E.O. (2000). The Glass Ceiling Hypothesis: A Comparative Study of the United States, Sweden, and Australia. Retrieved from: https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~wright/GenderGap.pdf

- The Federal Glass Ceiling Commission, Washington D.C. (1995). Good for Business: Making Full use of the Nation’s Human Capital. Retrieved from: https://witi.com/research/downloads/glassceiling.pdf

- United Nations Georgia. (2020). Our Work on the Sustainable Development Goals in Georgia. Retrieved from: https://georgia.un.org/en/sdgs